Difference between revisions of "Butcher series"

m (→Definitions: details) |

|||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

where $ T $ | where $ T $ | ||

| − | is the set of rooted | + | is the set of [[rooted tree]]s, $ a ( t ) \in \mathbf R $ |

is the coefficient for the series associated with the tree $ t $, | is the coefficient for the series associated with the tree $ t $, | ||

$ F ( t ) ( y ( x ) ) \in \mathbf R ^ {d} $ | $ F ( t ) ( y ( x ) ) \in \mathbf R ^ {d} $ | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

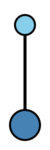

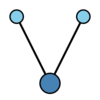

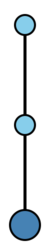

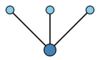

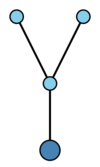

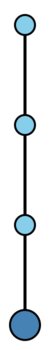

The rooted trees with at most four nodes are displayed in the table below. | The rooted trees with at most four nodes are displayed in the table below. | ||

| − | + | {| class="wikitable" | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | [[File:Rooted tree 0.svg|50px]] | + | | $t_1$ || $t_2=[t_1]$ || $ t_{3} = [t_{1},t_{1}]$ || $t_4 = [t_2]$ |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | [[File:Rooted tree 0.svg|50px]] || [[File:Rooted tree 10.svg|50px]] || [[File:Rooted tree 200.svg|100px]]|| [[File:Rooted tree 110.svg|50px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | + | {| class="wikitable" | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | | $t_5 =[t_1,t_1,t_1]$ || $t_6=[t_2,t_1]$ || $ t_{7} = [t_{3}]$ || $ t_{8} = [t_4]$ | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | | [[File:Rooted tree 3000.svg|100px]] || [[File:Rooted tree 2100.svg|100px]] || [[File:Rooted tree 1200.svg|100px]]|| [[File:Rooted tree 1110.svg|50px]] | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | |} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[File:Rooted tree 3000.svg|100px]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[File:Rooted tree 2100.svg|100px]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[File:Rooted tree 1200.svg|100px]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[File:Rooted tree 1110.svg|50px]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Using this bracket notation for rooted trees, one can recursively define elementary differentials, as follows. Let | Using this bracket notation for rooted trees, one can recursively define elementary differentials, as follows. Let | ||

| Line 149: | Line 123: | ||

as a Butcher series: | as a Butcher series: | ||

| − | + | \begin{equation} | |

| + | \label{eq:1} | ||

y ( x + h ) = \sum _ {i = 0 } ^ \infty y ^ {( i ) } ( x ) { | y ( x + h ) = \sum _ {i = 0 } ^ \infty y ^ {( i ) } ( x ) { | ||

\frac{h ^ {i} }{i! } | \frac{h ^ {i} }{i! } | ||

} = | } = | ||

| − | + | \end{equation} | |

$$ | $$ | ||

| Line 165: | Line 140: | ||

stage Runge–Kutta formula (cf. [[Runge–Kutta method|Runge–Kutta method]]) | stage Runge–Kutta formula (cf. [[Runge–Kutta method|Runge–Kutta method]]) | ||

| − | + | \begin{equation}\label{eq:2} | |

y _ {n + 1 } = y _ {n} + h \sum _ {i = 1 } ^ { s } b _ {i} k _ {i} , | y _ {n + 1 } = y _ {n} + h \sum _ {i = 1 } ^ { s } b _ {i} k _ {i} , | ||

| − | + | \end{equation} | |

$$ | $$ | ||

| Line 179: | Line 154: | ||

can be written as the Butcher series | can be written as the Butcher series | ||

| − | + | \begin{equation}\label{eq:3} | |

y _ {n + 1 } = \sum _ {t \in T } \alpha ( t ) \psi ( t ) F ( t ) ( y _ {n} ) { | y _ {n + 1 } = \sum _ {t \in T } \alpha ( t ) \psi ( t ) F ( t ) ( y _ {n} ) { | ||

\frac{h ^ {\rho ( t ) } }{\rho ( t ) ! } | \frac{h ^ {\rho ( t ) } }{\rho ( t ) ! } | ||

} , | } , | ||

| − | + | \end{equation} | |

| − | where the coefficients $ \psi ( t ) \in \mathbf R $, | + | where the coefficients $ \psi(t) \in \mathbf R $, |

| − | defined below, depend only on the rooted tree $ | + | defined below, depend only on the rooted tree $t$ |

| − | and the coefficients of the formula | + | and the coefficients of the formula \eqref{eq:2}. |

To define $ \psi ( t ) $, | To define $ \psi ( t ) $, | ||

| Line 210: | Line 185: | ||

$$ | $$ | ||

| − | where the product of $ \phi $' | + | where the product of $ \phi $'s in the bracket is taken component-wise. Then |

| − | s in the bracket is taken component-wise. Then | ||

$$ | $$ | ||

| Line 229: | Line 203: | ||

$$ | $$ | ||

| − | where, again, the product of $ \phi $' | + | where, again, the product of $ \phi $'s in the bracket is taken componentwise. |

| − | s in the bracket is taken componentwise. | ||

Assuming that $ y ( x ) = y _ {n} $ | Assuming that $ y ( x ) = y _ {n} $ | ||

| Line 236: | Line 209: | ||

for all trees $ t $ | for all trees $ t $ | ||

of order $ \leq p $, | of order $ \leq p $, | ||

| − | it follows immediately from | + | it follows immediately from \eqref{eq:1} and \eqref{eq:3} that |

$$ | $$ | ||

| Line 242: | Line 215: | ||

$$ | $$ | ||

| − | The order of | + | The order of \eqref{eq:2} is the largest such $p$. |

| + | |||

| + | ====Algebraic aspects==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Butcher series form a group, as they can be composed. This group is sometimes considered from the viewpoint of its Hopf algebra of functions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The modern understanding of this notion uses the notion of pre-Lie algebras, for the following reasons: | ||

| + | |||

| + | - The Lie algebra of analytic vector fields on the affine space $\RR^d$ comes by anti-symmetrization from the pre-Lie product given by the usual torsion-free and flat connection. | ||

| + | |||

| + | - The free pre-Lie algebra on one generator can be described as the vector space spanned by rooted trees, under some kind of grafting. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then, by the universal property of free pre-Lie algebras, the choice of any analytic vector field defines uniquely a morphism of pre-Lie algebras, which gives the "elementary differentials" associating a vector field to each rooted tree. | ||

====References==== | ====References==== | ||

<table> | <table> | ||

| − | <TR><TD valign="top">[a1]</TD> <TD valign="top"> J.C. Butcher, "The numerical analysis of ordinary differential equations" , Wiley (1987)</TD></TR> | + | <TR><TD valign="top">[a1]</TD> <TD valign="top"> J.C. Butcher, "The numerical analysis of ordinary differential equations" , Wiley (1987) {{ZBL|0616.65072}}</TD></TR> |

| − | <TR><TD valign="top">[a2]</TD> <TD valign="top"> E. Hairer, S.P. Nørsett, G. Wanner, "Solving ordinary differential equations I: nonstiff problems" , Springer (1987)</TD></TR> | + | <TR><TD valign="top">[a2]</TD> <TD valign="top"> E. Hairer, S.P. Nørsett, G. Wanner, "Solving ordinary differential equations I: nonstiff problems" , Springer (1987) {{ZBL|0638.65058}}</TD></TR> |

</table> | </table> | ||

Latest revision as of 08:28, 12 November 2023

B-series

Let $ y : \mathbf R \rightarrow {\mathbf R ^ {d} } $ be an analytic function satisfying an ordinary differential equation $ y ^ \prime ( x ) = f ( y ( x ) ) $. A Butcher series for $ y $ is a series of the form

$$ B ( a,y ( x ) ) = \sum _ {t \in T } a ( t ) F ( t ) ( y ( x ) ) { \frac{h ^ {\rho ( t ) } }{\rho ( t ) ! } } , $$

where $ T $ is the set of rooted trees, $ a ( t ) \in \mathbf R $ is the coefficient for the series associated with the tree $ t $, $ F ( t ) ( y ( x ) ) \in \mathbf R ^ {d} $ is the elementary differential associated with the tree $ t $, $ h \in \mathbf R $ is a stepsize or $ x $- increment, and $ \rho ( t ) $, often called the order of the tree $ t $, is the number of nodes in the tree $ t $. All terms will be defined below. For a more thorough discussion of Butcher series, see [a1] or [a2].

Definitions

A tree is a connected acyclic graph (cf. also Graph). A rooted tree is a tree with a distinguished node, called the root (which is drawn at the bottom of the sample trees in the Table). Two rooted trees $t$ and $\widehat{t}$ are isomorphic (i.e. equivalent) if and only if there is a bijection $\sigma $ from the nodes of $t$ to the nodes of $\widehat{t}$ such that $ \sigma $ maps the root of $ t $ to the root of $ {\widehat{t} } $ and any two nodes $ n _ {1} $ and $ n _ {2} $ are connected by an edge in $ t $ if and only if $ \sigma ( n _ {1} ) $ and $ \sigma ( n _ {2} ) $ are connected by an edge in $ {\widehat{t} } $.

The following bracket notation for rooted trees is very useful. Let $\bullet$ be the tree with one node. For rooted trees $ t_{1} \dots t _ {m} $ with $ \rho ( t _ {i} ) \geq 1 $ for $ i = 1 \dots m $, let $ t = [ t _ {1} \dots t _ {m} ] $ be the rooted tree formed by connecting a new root to the roots of each of $ t _ {1} \dots t _ {m} $. Clearly, $ \rho ( t ) = 1 + \sum _ {i = 1 } ^ {m} \rho ( t _ {i} ) $ and any rooted tree formed by permuting the subtrees $ t _ {1} \dots t _ {m} $ of $ t $ is isomorphic to $ t $.

The rooted trees with at most four nodes are displayed in the table below.

| $t_1$ | $t_2=[t_1]$ | $ t_{3} = [t_{1},t_{1}]$ | $t_4 = [t_2]$ |

|

|

|

|

| $t_5 =[t_1,t_1,t_1]$ | $t_6=[t_2,t_1]$ | $ t_{7} = [t_{3}]$ | $ t_{8} = [t_4]$ |

|

|

|

|

Using this bracket notation for rooted trees, one can recursively define elementary differentials, as follows. Let

$$ F ( \emptyset ) ( y ( x ) ) = y ( x ) , \quad F ( \bullet ) ( y ( x ) ) = f ( y ( x ) ) , $$

and, for $ t = [ t _ {1} \dots t _ {m} ] $ with $ \rho ( t _ {i} ) \geq 1 $ for $ i = 1 \dots m $,

$$ F ( t ) ( y ( x ) ) = $$

$$ = f ^ {( m ) } ( y ( x ) ) ( F ( t _ {1} ) ( y ( x ) ) \dots F ( t _ {m} ) ( y ( x ) ) ) , $$

where $ f ^ {( m ) } ( y ( x ) ) $, the $ m $ th derivative of $ f $ with respect to $ y $, is a multi-linear mapping.

Since $ y ( x ) $ satisfies $ y ^ \prime ( x ) = f ( y ( x ) ) $, it is not hard to show that

$$ y ^ {( i ) } ( x ) = \sum _ {t \in T _ {i} } \alpha ( t ) F ( t ) ( y ( x ) ) , $$

where $ y ^ {( i ) } ( x ) $ is the $ i $ th derivative of $ y $ with respect to $ x $, $ T _ {i} = \{ {t \in T } : {\rho ( t ) = i } \} $, and $ \alpha ( t ) $ is the number of distinct ways of labeling the nodes of $ t $ with the integers $ \{ 1 \dots \rho ( t ) \} $ such that the labels increase as you follow any path from the root to a leaf of $ t $. Consequently, one can write the Taylor series for $ y ( x ) $ as a Butcher series:

\begin{equation} \label{eq:1} y ( x + h ) = \sum _ {i = 0 } ^ \infty y ^ {( i ) } ( x ) { \frac{h ^ {i} }{i! } } = \end{equation}

$$ = \sum _ {t \in T } \alpha ( t ) F ( t ) ( y ( x ) ) { \frac{h ^ {\rho ( t ) } }{\rho ( t ) ! } } . $$

The importance of Butcher series stems from their use to derive and to analyze numerical methods for differential equations. For example, consider the $ s $- stage Runge–Kutta formula (cf. Runge–Kutta method)

\begin{equation}\label{eq:2} y _ {n + 1 } = y _ {n} + h \sum _ {i = 1 } ^ { s } b _ {i} k _ {i} , \end{equation}

$$ k _ {i} = f \left ( y _ {n} + h \sum _ {j = 1 } ^ { s } a _ {ij } k _ {j} \right ) , $$

for the ordinary differential equation $ y ^ \prime ( x ) = f ( y ( x ) ) $. Let $ b = ( b _ {1} \dots b _ {s} ) ^ {T} \in \mathbf R ^ {s} $ be the vector of weights and $ A = [ a _ {ij } ] \in \mathbf R ^ {s \times s } $ the coefficient matrix for (a2). Then it can be shown that $ y _ {n + 1 } $ can be written as the Butcher series

\begin{equation}\label{eq:3} y _ {n + 1 } = \sum _ {t \in T } \alpha ( t ) \psi ( t ) F ( t ) ( y _ {n} ) { \frac{h ^ {\rho ( t ) } }{\rho ( t ) ! } } , \end{equation}

where the coefficients $ \psi(t) \in \mathbf R $, defined below, depend only on the rooted tree $t$ and the coefficients of the formula \eqref{eq:2}.

To define $ \psi ( t ) $, first let

$$ \phi ( \emptyset ) = ( 1 \dots 1 ) ^ {T} \in \mathbf R ^ {s} , $$

$$ \phi ( \bullet ) = A \phi ( \emptyset ) , $$

and then, for $ t = [ t _ {1} \dots t _ {m} ] $ with $ \rho ( t _ {i} ) \geq 1 $ for $ i = 1 \dots m $, define $ \phi ( t ) $ recursively by

$$ \phi ( t ) = \rho ( t ) A ( \phi ( t _ {1} ) \dots \phi ( t _ {m} ) ) , $$

where the product of $ \phi $'s in the bracket is taken component-wise. Then

$$ \psi ( \emptyset ) = 1, $$

$$ \psi ( \bullet ) = \sum _ {i = 1 } ^ { s } b _ {i} , $$

and, for $ t = [ t _ {1} \dots t _ {m} ] $ with $ \rho ( t _ {i} ) \geq 1 $ for $ i = 1 \dots m $,

$$ \psi ( t ) = \rho ( t ) b ^ {T} ( \phi ( t _ {1} ) \dots \phi ( t _ {m} ) ) , $$

where, again, the product of $ \phi $'s in the bracket is taken componentwise.

Assuming that $ y ( x ) = y _ {n} $ and that $ \psi ( t ) = 1 $ for all trees $ t $ of order $ \leq p $, it follows immediately from \eqref{eq:1} and \eqref{eq:3} that

$$ y _ {n + 1 } = y ( x + h ) + {\mathcal O} ( h ^ {p + 1 } ) . $$

The order of \eqref{eq:2} is the largest such $p$.

Algebraic aspects

The Butcher series form a group, as they can be composed. This group is sometimes considered from the viewpoint of its Hopf algebra of functions.

The modern understanding of this notion uses the notion of pre-Lie algebras, for the following reasons:

- The Lie algebra of analytic vector fields on the affine space $\RR^d$ comes by anti-symmetrization from the pre-Lie product given by the usual torsion-free and flat connection.

- The free pre-Lie algebra on one generator can be described as the vector space spanned by rooted trees, under some kind of grafting.

Then, by the universal property of free pre-Lie algebras, the choice of any analytic vector field defines uniquely a morphism of pre-Lie algebras, which gives the "elementary differentials" associating a vector field to each rooted tree.

References

| [a1] | J.C. Butcher, "The numerical analysis of ordinary differential equations" , Wiley (1987) Zbl 0616.65072 |

| [a2] | E. Hairer, S.P. Nørsett, G. Wanner, "Solving ordinary differential equations I: nonstiff problems" , Springer (1987) Zbl 0638.65058 |

Butcher series. Encyclopedia of Mathematics. URL: http://encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=Butcher_series&oldid=52562