Difference between revisions of "User:Nikita2/sandbox"

(Created page with "<asy> import graph; size(200,IgnoreAspect); real f(real x) {return sin(x);}; bool3 branch(real x) { static int lastsign=0; //if(x == 0) return false; int sign=sgn(x); ...") |

m (→AsymptotePlay) |

||

| (16 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | A mapping $\varphi:D\to D'$ possesses Luzin's $\mathcal N$-property if the image of every set of measure zero is a set of measure zero. A mapping $\varphi$ possesses Luzin's $\mathcal N{}^{-1}$-property if the preimage of every set of measure zero is a set of measure zero. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Briefly'' | ||

| + | \begin{equation*} | ||

| + | \mathcal N\text{-property:}\quad \Sigma\subset D, |\Sigma| = 0 \Rightarrow |\varphi(\Sigma)|=0, | ||

| + | \end{equation*} | ||

| + | \begin{equation*} | ||

| + | \mathcal N{}^{-1}\text{-property:} \quad M \subset D, |M| = 0 \Rightarrow |\varphi^{-1}(M)|=0. | ||

| + | \end{equation*} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ====$\mathcal N$-property of a function $f$ on an interval $[a,b]$==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let $f:[a,b]\to \mathbb R$ be a measurable function. In this case the definition is following: | ||

| + | ''For any set $E\subset[a,b]$ of measure zero ($|E|=0$), the image of this set, $f(E)$, also has measure zero.'' | ||

| + | It was introduced by N.N. Luzin in 1915 (see [[#References|[1]]]). The following assertions hold. | ||

| + | # A function $f\not\equiv \operatorname{const}$ on $[a,b]$ such that $f'(x)=0 $ almost-everywhere on $[a,b]$ (see for example [[Cantor_ternary_function|Cantor ternary function]]) does not have the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property. | ||

| + | # If $f$ does not have the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property, then on $[a,b]$ there is a [[Perfect set|perfect set]] $P$ of measure zero such that $|f(P)|>0$. | ||

| + | # An [[Absolutely_continuous_function#Absolute_continuity_of_a_function|absolutely continuous function]] has the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property. | ||

| + | # If $f$ has the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property and has [[Function_of_bounded_variation#Classical_definition|bounded variation]] on $[a,b]$ (as well as being continuous on $[a,b]$), then $f$ is absolutely continuous on $[a,b]$ (the Banach–Zaretskii theorem). | ||

| + | # If $f$ does not decrease on $[a,b]$ and $f'$ is finite on $[a,b]$, then $f$ has the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property. | ||

| + | # In order that $f(E)$ be measurable for every measurable set $E\subset[a,b]$ it is necessary and sufficient that $f$ have the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property on $[a,b]$. | ||

| + | # A function $f$ that has the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property has a derivative $f'$ on the set for which any non-empty [[Portion|portion]] of it has positive measure. | ||

| + | # For any perfect nowhere-dense set $P\subset[a,b]$ there is a function $f$ having the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property on $[a,b]$ and such that $f'$ does not exist at any point of $P$. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The concept of Luzin's <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105044.png" />-property can be generalized to functions of several variables and functions of a more general nature, defined on measure spaces. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====References==== | ||

| + | <table><TR><TD valign="top">[1]</TD> <TD valign="top"> N.N. Luzin, "The integral and trigonometric series" , Moscow-Leningrad (1915) (In Russian) (Thesis; also: Collected Works, Vol. 1, Moscow, 1953, pp. 48–212) {{MR|}} {{ZBL|}} </TD></TR></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ====Comments==== | ||

| + | There is another property intimately related to the Luzin <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105045.png" />-property. A function <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105046.png" /> continuous on an interval <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105047.png" /> has the Banach <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105049.png" />-property if for all Lebesgue-measurable sets <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105050.png" /> and all <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105051.png" /> is a <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105052.png" /> such that | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table class="eq" style="width:100%;"> <tr><td valign="top" style="width:94%;text-align:center;"><img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105053.png" /></td> </tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is clearly stronger than the <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105054.png" />-property. S. Banach proved that a function <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105055.png" /> has the <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105056.png" />-property (respectively, the <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105057.png" />-property) if and only if (respectively, only if — see below for the missing "if" ) the inverse image <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105058.png" /> is finite (respectively, is at most countable) for almost-all <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105059.png" /> in <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105060.png" />. For classical results on the <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105061.png" />- and <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105062.png" />-properties, see [[#References|[a3]]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Recently a powerful extension of these results has been given by G. Mokobodzki (cf. [[#References|[a1]]], [[#References|[a2]]]), allowing one to prove deep results in potential theory. Let <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105063.png" /> and <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105064.png" /> be two compact metrizable spaces, <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105065.png" /> being equipped with a probability measure <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105066.png" />. Let <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105067.png" /> be a Borel subset of <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105068.png" /> and, for any Borel subset <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105069.png" /> of <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105070.png" />, define the subset <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105071.png" /> of <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105072.png" /> by <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105073.png" /> (if <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105074.png" /> is the graph of a mapping <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105075.png" />, then <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105076.png" />). The set <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105077.png" /> is said to have the property (N) (respectively, the property (S)) if there exists a measure <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105078.png" /> on <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105079.png" /> (here depending on <img align="absmiddle" border | ||

| + | ="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105080.png" />) such that for all <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105081.png" />, | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table class="eq" style="width:100%;"> <tr><td valign="top" style="width:94%;text-align:center;"><img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105082.png" /></td> </tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | (respectively, for all <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105083.png" /> there is a <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105084.png" /> such that for all <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105085.png" /> one has | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table class="eq" style="width:100%;"> <tr><td valign="top" style="width:94%;text-align:center;"><img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105086.png" /></td> </tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105087.png" /> has the property (N) (respectively, the property (S)) if and only if the section <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105088.png" /> of <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105089.png" /> is at most countable (respectively, is finite) for almost-all <img align="absmiddle" border="0" src="https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/legacyimages/l/l061/l061050/l06105090.png" />. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====References==== | ||

| + | <table><TR><TD valign="top">[a1]</TD> <TD valign="top"> C. Dellacherie, D. Feyel, G. Mokobodzki, "Intégrales de capacités fortement sous-additives" , ''Sem. Probab. Strasbourg XVI'' , ''Lect. notes in math.'' , '''920''' , Springer (1982) pp. 8–28 {{MR|0658670}} {{ZBL|0496.60076}} </TD></TR><TR><TD valign="top">[a2]</TD> <TD valign="top"> A. Louveau, "Minceur et continuité séquentielle des sous-mesures analytiques fortement sous-additives" , ''Sem. Initiation à l'Analyse'' , '''66''' , Univ. P. et M. Curie (1983–1984) {{MR|}} {{ZBL|0587.28003}} </TD></TR><TR><TD valign="top">[a3]</TD> <TD valign="top"> S. Saks, "Theory of the integral" , Hafner (1952) (Translated from French) {{MR|0167578}} {{ZBL|1196.28001}} {{ZBL|0017.30004}} {{ZBL|63.0183.05}} </TD></TR><TR><TD valign="top">[a4]</TD> <TD valign="top"> E. Hewitt, K.R. Stromberg, "Real and abstract analysis" , Springer (1965) {{MR|0188387}} {{ZBL|0137.03202}} </TD></TR></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

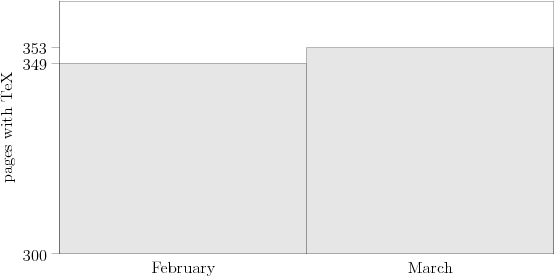

| + | ===AsymptotePlay=== | ||

| + | |||

<asy> | <asy> | ||

import graph; | import graph; | ||

| − | |||

| − | real | + | size(400,200,IgnoreAspect); |

| + | |||

| + | int n=2; | ||

| + | |||

| + | real[] a=new real[n]; | ||

| + | real[] x=new real[n]; | ||

| + | |||

| + | //real[] x=sequence(n); | ||

| − | + | string[] month={"Jan","February","March","April","May","Jun","Jul","Aug","Sep","Oct","Nov","Dec"}; | |

| + | |||

| + | a[0]=349; //February | ||

| + | a[1]=353; //March | ||

| + | a[2]=363; //April | ||

| + | a[3]=353; //May | ||

| + | a[4]=353; //June | ||

| + | |||

| + | void mbox(real m, real c) | ||

{ | { | ||

| − | + | path g=box((m-0.5,0),(m+0.5,c)); | |

| − | + | filldraw(g,lightgrey); | |

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

} | } | ||

| + | for(int i=0; i<n;++i){x[i]=i+0.5;} | ||

| + | for(int i=0; i < n; ++i){ mbox(i,a[i]);} | ||

| + | //draw((-0.5,300)--(n-0.5,300)); | ||

| + | draw(box((-0.5,300),(n-0.5,a[n]+2))); | ||

| + | limits((-0.5,300),(n-0.5,a[n]+2),Crop); | ||

| − | + | xaxis(xmin=0,Bottom,LeftTicks(Step=1,new string(real y) {return month[round(y+1 % 12)];})); | |

| − | + | yaxis("pages with TeX",Left,LeftTicks(DefaultFormat, new real[] {300,a[0],a[1]})); | |

</asy> | </asy> | ||

| + | |||

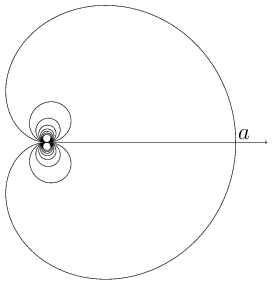

| + | ===FigurePlay=== | ||

| + | <span id="Fig1", bg="black"> | ||

| + | [[File:Cochleoid-1.png| right| frame| Figure 1. The cochleoid ([[Media:Cochleoid-1.pdf|pdf]]) ]] | ||

| + | </span> | ||

Latest revision as of 07:08, 3 March 2013

A mapping $\varphi:D\to D'$ possesses Luzin's $\mathcal N$-property if the image of every set of measure zero is a set of measure zero. A mapping $\varphi$ possesses Luzin's $\mathcal N{}^{-1}$-property if the preimage of every set of measure zero is a set of measure zero.

Briefly \begin{equation*} \mathcal N\text{-property:}\quad \Sigma\subset D, |\Sigma| = 0 \Rightarrow |\varphi(\Sigma)|=0, \end{equation*} \begin{equation*} \mathcal N{}^{-1}\text{-property:} \quad M \subset D, |M| = 0 \Rightarrow |\varphi^{-1}(M)|=0. \end{equation*}

$\mathcal N$-property of a function $f$ on an interval $[a,b]$

Let $f:[a,b]\to \mathbb R$ be a measurable function. In this case the definition is following: For any set $E\subset[a,b]$ of measure zero ($|E|=0$), the image of this set, $f(E)$, also has measure zero. It was introduced by N.N. Luzin in 1915 (see [1]). The following assertions hold.

- A function $f\not\equiv \operatorname{const}$ on $[a,b]$ such that $f'(x)=0 $ almost-everywhere on $[a,b]$ (see for example Cantor ternary function) does not have the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property.

- If $f$ does not have the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property, then on $[a,b]$ there is a perfect set $P$ of measure zero such that $|f(P)|>0$.

- An absolutely continuous function has the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property.

- If $f$ has the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property and has bounded variation on $[a,b]$ (as well as being continuous on $[a,b]$), then $f$ is absolutely continuous on $[a,b]$ (the Banach–Zaretskii theorem).

- If $f$ does not decrease on $[a,b]$ and $f'$ is finite on $[a,b]$, then $f$ has the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property.

- In order that $f(E)$ be measurable for every measurable set $E\subset[a,b]$ it is necessary and sufficient that $f$ have the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property on $[a,b]$.

- A function $f$ that has the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property has a derivative $f'$ on the set for which any non-empty portion of it has positive measure.

- For any perfect nowhere-dense set $P\subset[a,b]$ there is a function $f$ having the Luzin $\mathcal N$-property on $[a,b]$ and such that $f'$ does not exist at any point of $P$.

The concept of Luzin's  -property can be generalized to functions of several variables and functions of a more general nature, defined on measure spaces.

-property can be generalized to functions of several variables and functions of a more general nature, defined on measure spaces.

References

| [1] | N.N. Luzin, "The integral and trigonometric series" , Moscow-Leningrad (1915) (In Russian) (Thesis; also: Collected Works, Vol. 1, Moscow, 1953, pp. 48–212) |

Comments

There is another property intimately related to the Luzin  -property. A function

-property. A function  continuous on an interval

continuous on an interval  has the Banach

has the Banach  -property if for all Lebesgue-measurable sets

-property if for all Lebesgue-measurable sets  and all

and all  is a

is a  such that

such that

|

This is clearly stronger than the  -property. S. Banach proved that a function

-property. S. Banach proved that a function  has the

has the  -property (respectively, the

-property (respectively, the  -property) if and only if (respectively, only if — see below for the missing "if" ) the inverse image

-property) if and only if (respectively, only if — see below for the missing "if" ) the inverse image  is finite (respectively, is at most countable) for almost-all

is finite (respectively, is at most countable) for almost-all  in

in  . For classical results on the

. For classical results on the  - and

- and  -properties, see [a3].

-properties, see [a3].

Recently a powerful extension of these results has been given by G. Mokobodzki (cf. [a1], [a2]), allowing one to prove deep results in potential theory. Let  and

and  be two compact metrizable spaces,

be two compact metrizable spaces,  being equipped with a probability measure

being equipped with a probability measure  . Let

. Let  be a Borel subset of

be a Borel subset of  and, for any Borel subset

and, for any Borel subset  of

of  , define the subset

, define the subset  of

of  by

by  (if

(if  is the graph of a mapping

is the graph of a mapping  , then

, then  ). The set

). The set  is said to have the property (N) (respectively, the property (S)) if there exists a measure

is said to have the property (N) (respectively, the property (S)) if there exists a measure  on

on  (here depending on

(here depending on  ) such that for all

) such that for all  ,

,

|

(respectively, for all  there is a

there is a  such that for all

such that for all  one has

one has

|

Now  has the property (N) (respectively, the property (S)) if and only if the section

has the property (N) (respectively, the property (S)) if and only if the section  of

of  is at most countable (respectively, is finite) for almost-all

is at most countable (respectively, is finite) for almost-all  .

.

References

| [a1] | C. Dellacherie, D. Feyel, G. Mokobodzki, "Intégrales de capacités fortement sous-additives" , Sem. Probab. Strasbourg XVI , Lect. notes in math. , 920 , Springer (1982) pp. 8–28 MR0658670 Zbl 0496.60076 |

| [a2] | A. Louveau, "Minceur et continuité séquentielle des sous-mesures analytiques fortement sous-additives" , Sem. Initiation à l'Analyse , 66 , Univ. P. et M. Curie (1983–1984) Zbl 0587.28003 |

| [a3] | S. Saks, "Theory of the integral" , Hafner (1952) (Translated from French) MR0167578 Zbl 1196.28001 Zbl 0017.30004 Zbl 63.0183.05 |

| [a4] | E. Hewitt, K.R. Stromberg, "Real and abstract analysis" , Springer (1965) MR0188387 Zbl 0137.03202 |

AsymptotePlay

FigurePlay

Nikita2/sandbox. Encyclopedia of Mathematics. URL: http://encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=Nikita2/sandbox&oldid=29091